Early on in the Covid-19 pandemic, when drugs were being developed and tested in hopes of a vaccine or cure, two Georgia Tech physicists, who often collaborate, bridged their research and teamed up to study the possible arrhythmic effects of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), which was being considered by some, at the time, as a potential treatment.

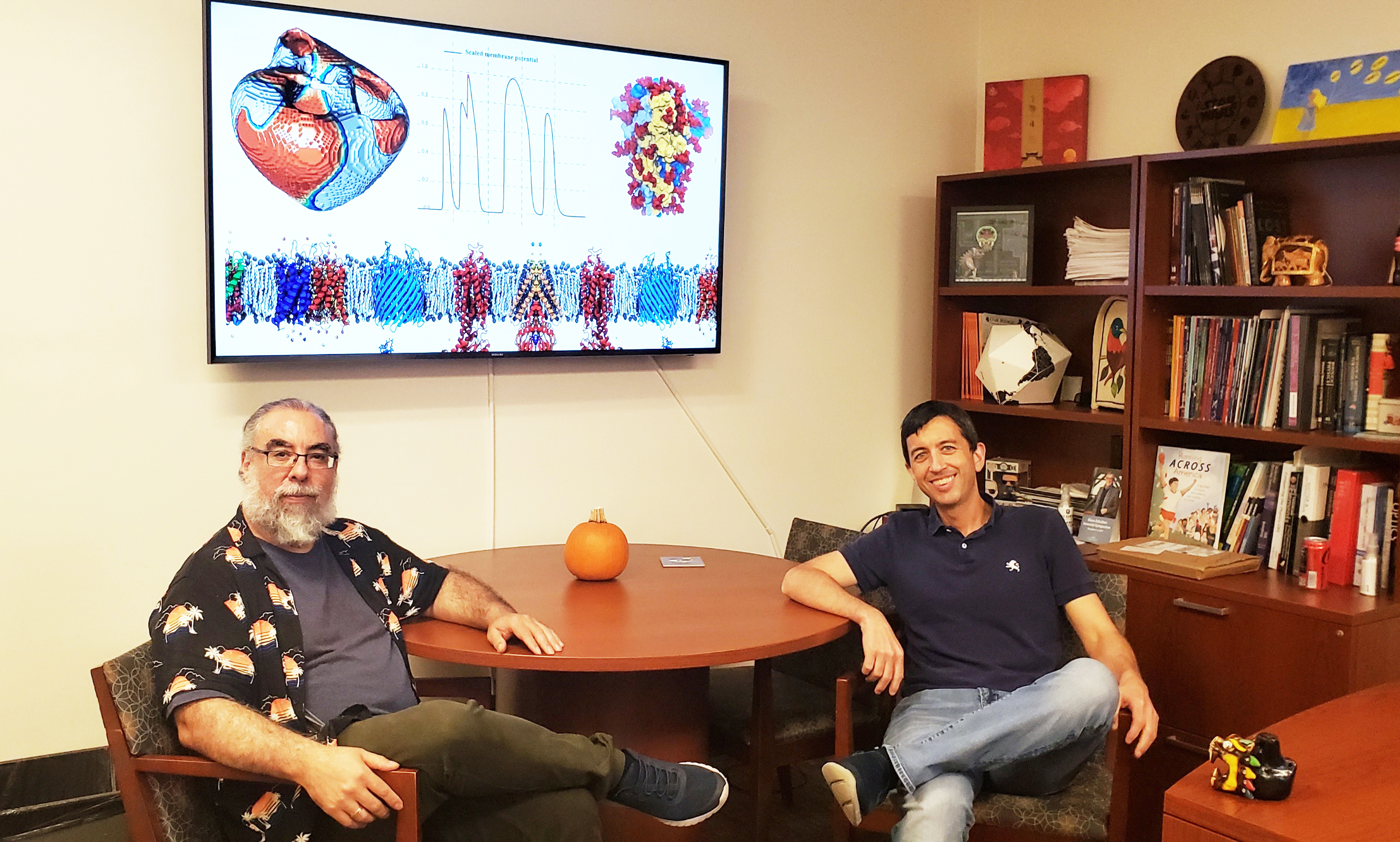

School of Physics Professor and Adjunct Professor of Biology Flavio Fenton and Associate Professor James (JC) Gumbart published two papers on the subject, illustrating challenges to determining the new safety profile of repurposed drugs.

“We showed theoretically and experimentally that, indeed, at high concentrations the drug was pro-arrhythmic and could initiate arrhythmias,” said Fenton.

“As soon as there were reports about the use of HCQ and connection with some patients with arrhythmias, we started to investigate,” Fenton added. This was around March 2020. “We got the first paper out in May.”

Explaining how their research areas differ, Gumbart shared, “My research uses atomistic molecular dynamics simulations to understand the relationship between structure and function of proteins.” He added, “While we work on a number of systems, themes in the lab include outer-membrane proteins in Gram-negative bacteria as well as proteins in viruses, most notably hepatitis B virus. We also pivoted part of the lab’s efforts to SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes Covid-19) during the pandemic.”

Beyond the work with Fenton, Gumbart’s lab has published seven papers on SARS-CoV-2 proteins. “The most recent of these was the largest simulation we’ve ever run, a so-called ‘potential of mean force’ calculation to determine the energetics of opening the spike protein,” Gumbart said. “For this, we used Summit at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, one of the fastest supercomputers in the world.” The team’s work was published in Communications Biology.

“My work is more on the macroscale, cells to tissue and organ, while JC’s is more on the molecular scale,” Fenton explained. “There are several orders of magnitude in both time and space separating our research.”

Ten years ago…

Fenton is also an adjunct professor of Biology. Before he arrived at Georgia Tech, he was director of Electrophysiology Research at the Beth Israel Medical Center, now Mount Sinai Beth Israel, in New York City for five years, and then research scientist at Cornell University in the College of Veterinary Medicine for six years. However, with his training as a physicist, his calling was to join a physics department and train physics students to work on nonlinear dynamics and biophysics, which led him to the opportunity at Georgia Tech, where he and Gumbart met.

Gumbart, who also serves as associate director of the Quantitative Biosciences Ph.D. program at Georgia Tech, said what ultimately brought him to Georgia Tech was the extraordinary research being done in the sciences, particularly in the Physics of Living Systems group, of which he and Fenton are both faculty members. “I didn’t know Flavio before, but after arriving at Georgia Tech in January 2013, he and I quickly bonded over our research and shared love for NFL football, with my team being the Chicago Bears, and his the Pittsburgh Steelers.”

Collaboration, cross pollination, and a love story

“The disparate scales on which we work — my lab on individual proteins and Flavio’s on entire organs — makes it hard to bridge the gap,” said Gumbart. “But we are always on the lookout for new opportunities. Even if we haven’t collaborated very often in research, we often discuss other things such as outreach and teaching,” He added. “For example, when I taught my first Introductory Physics class, I sat in on Flavio’s section every morning before my own to observe how to best convey the difficult concepts being covered that day.”

Their lab members are also frequent collaborators, partly due to the fact that their offices and labs are close to each other. “There has been some cross pollination,” Fenton smiled. “With one of my Ph.D. students transferring to JC’s lab to do his Ph.D., and one of his undergraduate students came to my lab to do his. Fenton added that two students from the differing labs ended up getting married, and now both work at the FDA. “Currently, we are co-mentoring an undergraduate, and we have a married couple who joined our labs— one partner in each lab,” Fenton added.

Productive publishers

Although there was no competition or a particular number slated as a goal, Fenton and Gumbart, realized through a conversation that their decade of research at Georgia Tech has resulted in 100 published papers for each of them and their lab members, in journals like Nature and Nature Communications, PNAS, and Physical Review Letters.

Gumbart added that some years resulted in more papers than others, but that published research in his lab has increased in recent years. “17 in 2021, and 17 — so far — in 2022,” Gumbart said. “We were fortunate that computational research was minimally impacted by the switch to remote work during the Covid pandemic. We also have benefited greatly from a long-term trend in the increasing recognition of the role simulations can play in understanding biological systems at the molecular scale, which has led to more collaborations and projects than ever. “

Both professors point to students as a key part of these collaborative opportunities. “GT grads and undergrads are the best,” Fenton said. “I could not have done the studies and obtained the results we have published without them.”

“My research has expanded in part through the wealth of collaborative opportunities I’ve found here,” Gumbart shared, adding that colleagues at other schools also recognize graduate students as a key strength of the Georgia Tech research program.

Alligators, Santa, and Rick and Morty

Years of interaction with colleagues and students have provided several memories in addition to collaboration. Fenton recalled what he described as a “fun memory” that took an unexpected turn.

“One day while having lunch with a postdoc of Professor Dan Goldman — Henry Astley, now a professor at University of Akron — we were talking about alligators and began asking questions about the physics behind their unique physiology,” Fenton said. “Our discussion led us to talks with Professor Tomasz Owerkowicz at California State University at San Bernardino, who sent us alligators (with approved protocols) and we performed experiments that resulted in a paper, "Defibrillate You Later, Alligator: Q10 Scaling and Refractoriness Keeps Alligators from Fibrillation." So our casual lunch resulted in a very interesting study.”

As a result of studies like these, Fenton and cohorts have been able to develop new methods for low energy defibrillation including a theory to "teleport" spiral waves of electrical activity with a small stimulus that can terminate arrhythmias. “But what we are most excited about,” said Fenton, “is that for the past year we have begun performing experiments in explanted hearts from patients that receive a new heart at Emory University’s Hospital — we are one of the few groups in the world doing this.”

The next 10 years…

Gumbart and Fenton said that while they look forward to continuing their friendship and (at least) another 100 papers each, they also hope to continue working together and co-mentoring students. “I believe this will be easy to do, as JC loves doing research,” Fenton said. “I can always count on finding him in his office working late at night for a chat or discussion, and he is always game for trying new restaurants for dinner and having scientific discussions.”

Gumbart shared, “One of the great things about working with Flavio is how festive he is, whether dressing up for something new every Halloween or even Santa Claus at Christmas. Last year, he even convinced me to join him— we dressed up as Rick and Morty. I shudder a bit at the thought of what he’ll convince me to do next year!"

For More Information Contact

Writer:

Laurie E. Smith, College of Sciences

Editor and Contact:

Jess Hunt-Ralston

Director of Communications

College of Sciences at Georgia Tech