Editor's Note: This story by Victor Rogers was originally published on the Georgia Tech News Center on Aug. 8, 2018.

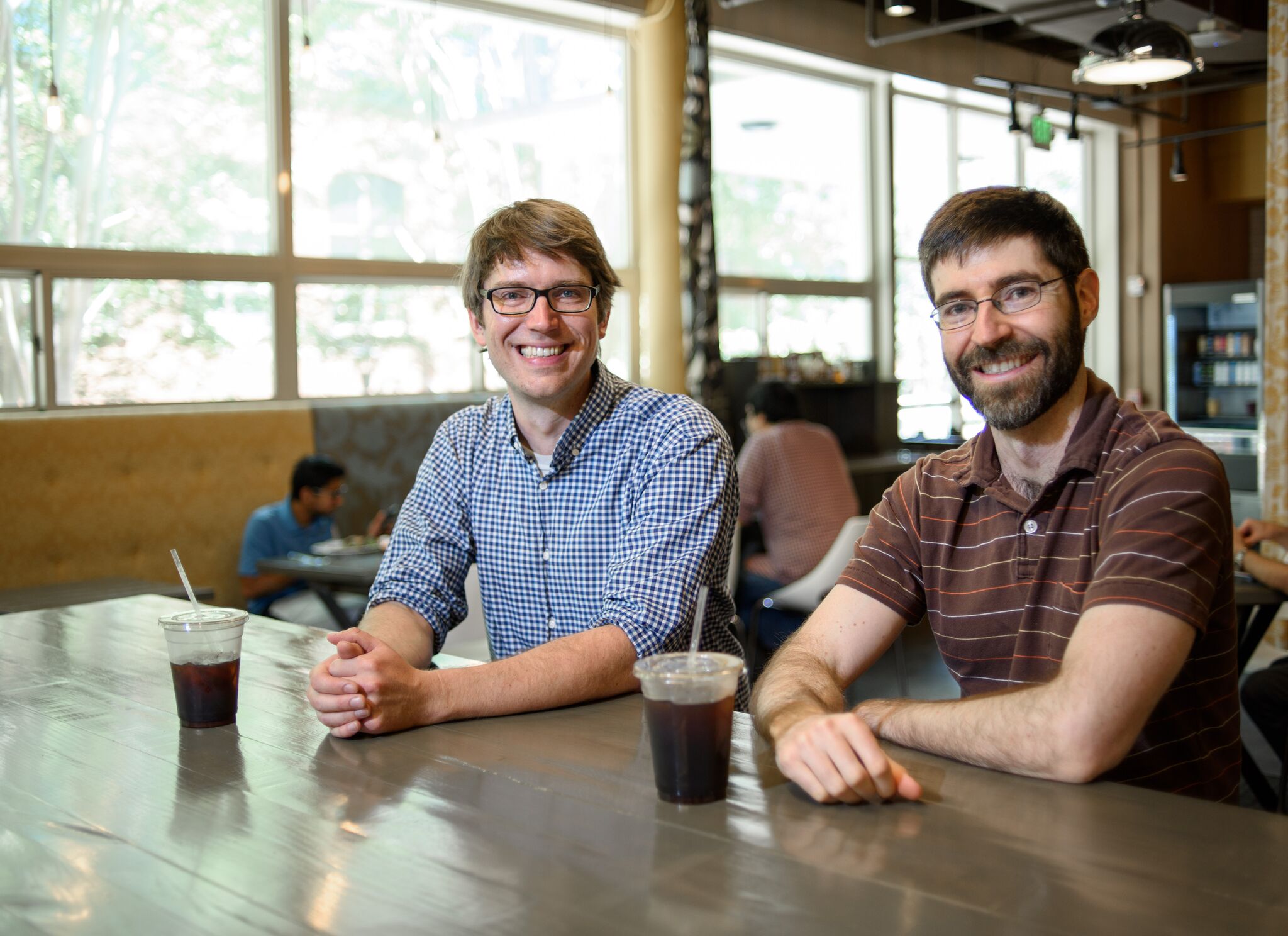

When Will Ratcliff and Peter Yunker first met for coffee they had no idea they would eventually collaborate on research that would be published in Nature Communications and Nature Physics.

Ratcliff, an assistant professor in the School of Biological Sciences, arrived at Tech in January 2014. Yunker, an assistant professor in the School of Physics, arrived in January of the following year.

“I met with [Physics Professor] Dan Goldman and told him about my interests in biophysics,” said Yunker. “He told me there’s another young guy who just arrived. You should contact him.”

Yunker reached out to Ratcliff, and the two began meeting weekly for coffee in the basement of the College of Computing.

“I think our conversations for a solid six months were just about friend stuff,” Ratcliff said. “We talked about science, but we weren’t actively pursuing projects. We were just hanging out and getting to know each other.”

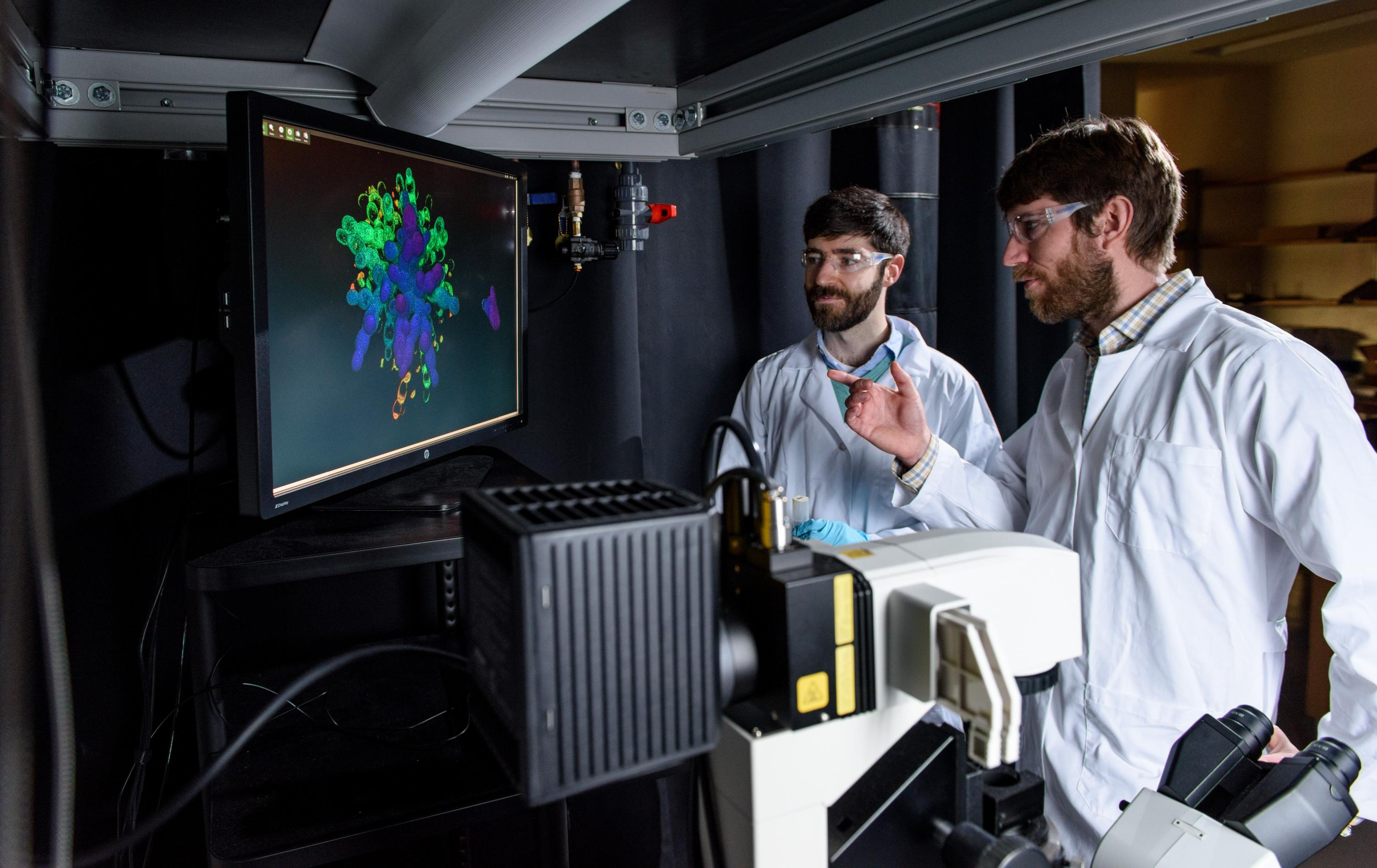

Yunker said they discussed ideas about the evolution of multicellularity.

“Will would talk a little about the biology of the evolution of multicellularity. And then we would pivot, and I would talk about the physics of multicellularity,” Yunker said.

Though coming from different disciplines — biology and physics — Ratcliff and Yunker quickly recognized some common ground.

“I would say, ‘There’s this thing in biology where this needs to happen,’ and he would say ‘there’s this thing in physics where this needs to happen,’” Ratcliff said. “It would blow my mind because it was a totally different way of thinking about the things that I was already thinking about. It was incredibly exciting because there were these parallels coming from such different places, and they were describing the same overlapping material. I think we both could tell there was a lot of cool stuff to be done.”

The harder part was figuring out where the overlap was concrete so they could actually conduct experiments or write models.

“A lot of our conversations are brainstorming style,” Yunker said. “They’re less about knocking down ideas and more about: ‘Let’s get a lot of information out there so we can find where that concrete idea emerges.’”

The collaboration also eased the pressure of being a new faculty member.

“It’s nice to work with other people who are at a similar level, to bounce ideas off each other, talk about critical review, and vent about frustrations,” Yunker said. “The whole time I’ve been here I have always heard Georgia Tech is very supportive of collaboration. I’ve heard of other places where that support isn’t there when you’re still at the assistant professor level. I haven’t worried at all about if there will be trouble down the line if we collaborate. Instead, I see it as we’re doing the best science, and that’s what Georgia Tech wants.”

Ratcliff said, “That’s one of Georgia Tech’s real strengths. People really appreciate our collaboration. I hear from people in both communities — biology and physics. They appreciate not just the research, but also the strengthening of the bridge between the departments and the sense of community it builds.”

In addition to their research collaborations, Ratcliff and Yunker co-advise a Ph.D. student and a postdoc.

Collaboration Advice to New Faculty

Yunker and Ratcliff make collaboration look deceptively easy.

“Collaboration takes effort. It takes sustained interaction,” Ratcliff said. “There’s got to be a reason to do that because as new professors we’re super busy trying to get everything off the ground: get your lab running, get grants, write papers, design classes, do service work. We’re spread really thin. So, to have sustained interactions that are needed for a good collaboration, you have to prioritize it and want to do it.”

Yunker added, “One of the best approaches when starting a new collaboration is to either let it grow or die on its own. If the idea isn’t there or if you just don’t mesh, then forcing it is going to be difficult for everyone.”

Ratcliff has advice for new faculty who are interested in collaborating.

“It’s really exciting and valuable to have a close collaborator from a different discipline or with a different skillset,” he said. “To get that, I suggest forming collaborations with other professors who are about your age. Key reasons are you’re both at the same stage in your careers. You’re equals. Also, a new professor is likely to have time to form new collaborations. Lastly, new professors have startup funds and a large degree of flexibility. This is great for trying things that are risky.”

He also suggests attending receptions for new faculty.

“Talk to people outside of your discipline. Don’t spend all of your time at the mixer talking to your departmental colleagues,” Ratcliff said.

Developing a good collaboration can be transformational.

“Our collaboration has fundamentally reshaped the way I think about key problems in my field,” Ratcliff said. “I know how to think about the things I was trained to think about, but I had no idea how to think about things I wasn’t trained to think about.”

Yunker said, “Together we’re able to ask and answer more interesting questions. I was not versed at all on questions about evolutionary transitions and individuality. I wasn’t aware of all the open questions and problems there, and they’re fascinating. By coming together, we end up asking even more interesting questions and, hopefully, coming up with new approaches.”

Ratcliff said what made the collaboration work is that he and Yunker became friends.

“We enjoy hanging out. I look forward to having coffee,” Ratcliff said. “We have these exciting scientific discussions where it was obvious that there’s something there, but we had to make the ideas touch down to reality.”