There are a few things all mammals have in common. We all breathe air, drink water, and eat food, to name a few. Christina Ragan’s research homes in on the events surrounding one of the first experiences that bind us all together: being born.

“Everyone has had a mother at some point in their life,” says Ragan, who is a faculty member and academic professional in the School of Biological Sciences and the director of Outreach for the Undergraduate Program in Neuroscience at Tech. “We may all develop different diseases [later in life], but we've all had a mother.”

Ragan, who directs the Molecular Mechanisms of Mothering and Anxiety (MOMMA) Lab, is particularly interested in studying how the events of pregnancy and early parenthood may affect the mental health of both mothers and children.

“Mental health is one of those things that’s not always as obvious as other physical ailments. If you break your arm, you go to the doctor. If you have a heart attack, you would go to the doctor. But when you're feeling depressed or anxious, sometimes you don't always go and seek help,” Ragan explains. “We need better markers of mental health — if we can find some of those neurobiological markers, maybe that can help identify who's at risk.”

And after years of studying it, Ragan is about to become a parent herself, finding that “you can do as much research as you want, and you’re still going to find things that surprise you.”

Monitoring mental health

“I'm interested in the neurobiology of parental behavior — or what's going on in the brain when someone becomes a parent — and I focus on mothers,” Ragan says. One of her big interests is in postpartum anxiety.

“What happens with postpartum anxiety is that it just seems typical to most people. Of course, I’m going to worry about my kid, right? That's how they survive. But it becomes an issue when it's prolonged.

To better understand anxious mothers, Ragan studies animals. “The challenge with using non-human animals is we can't ask them, ‘how are you feeling today?’ But we have these other proxy measures.” By measuring how the animals respond to spaces that either induce anxiety (like a maze, high off the ground) or calm it (like a dark, enclosed space), Ragan can gain insights into their mental health

Throughout her career, Ragan has examined how things like exposure to certain medications or skin-to-skin contact impacts behavioral and neurobiological markers of anxiety in both maternal and postnatal rodents. One such project examined obsessive-compulsive behaviors in maternal rats and their offspring.

“Postpartum OCD is things like constantly checking to see if the baby's breathing, which again, plenty of parents do. But will you not leave the house because you're worried something's going to happen?”

Exposing rodents to clomipramine — an antidepressant commonly prescribed to treat OCD in humans — shortly after birth has been shown to induce OCD-like behaviors in rodents (like repetitively poking their heads in and out of holes in an enclosure) later in life. “But people had done this work only in male rats,” Ragan says.

When she studied the effects of this exposure on the behavior of maternal rats, they exhibited the same OCD-like behaviors that had been observed in male rats. Ragan says they were also “different in their nursing behaviors. Overall, the amount of time [spent nursing] was the same as the controls, but when it should have been at its highest — it was kind of shifted.”

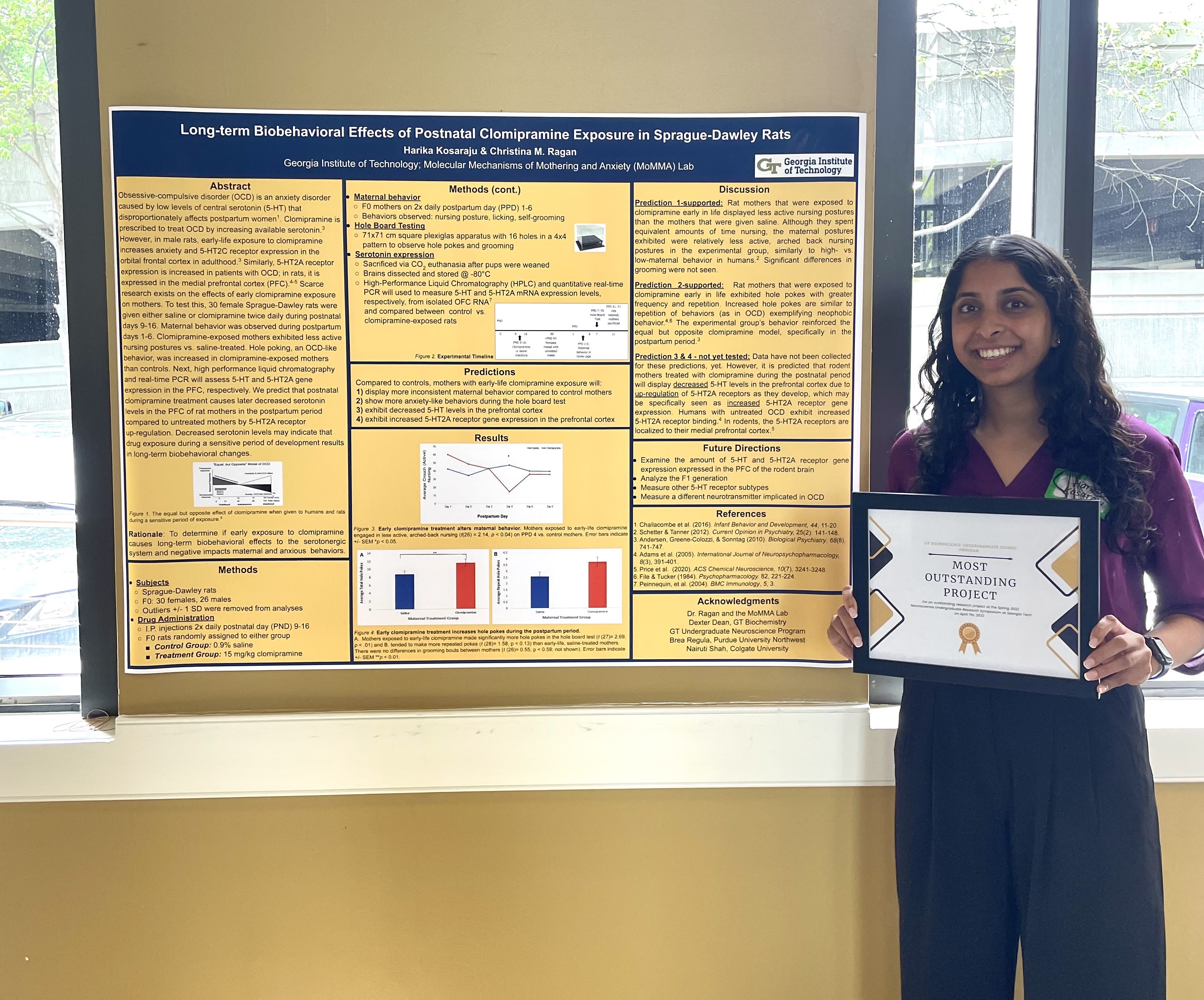

For the past year, Harika Kosaraju, an undergraduate studying neuroscience at Georgia Tech, has been following up on Ragan’s behavioral research. Kosaraju will dive deeper into this work in the fall, where she’ll be looking at how those conditions impact serotonin — a neurotransmitter commonly decreased with OCD — in decision-making areas of the brain, as well as how the molecular machinery cells use to produce serotonin are affected.

“I was initially really attracted to Dr. Ragan's projects because of this population that they were addressing, that I hadn't seen addressed in a lot of research,” says Kosaraju. “Focusing on a population that doesn't have a lot of research is so important — especially because of the stresses and risks of pregnancy and childbirth in the postpartum period.”

Putting theory into practice

Ragan’s husband Zachary Grieb, who is a Medical Science Liaison with Amneal Pharmaceuticals, also studied the neurobiology of parenthood, focusing primarily on the interplay between oxytocin and parenthood. The two met as trainees at Michigan State University, and after years of collaborating on their parenthood research, Grieb and Ragan will soon begin their own journey in parenthood.

“One of the things I remember [Christina] saying when we were dating was ‘I have to have a baby — I mean, we study this!’,” Grieb says.

“Exactly!” Ragan replied. “We have to put theory into practice. But you can research for years and years and years, and nothing can really prepare you for a child,” Ragan says.

“I think one of the things I’ve appreciated more about this process is how everything begins with the mother,” Grieb added. “Gestation — the mother and her experiences — those are [the baby’s] initial paths.

And while that may sound overwhelming, both Ragan and Grieb have some related advice for new parents.

“The newborn brain is as plastic as it ever will be — you have the most cells you’ll ever have,” Grieb says. “One of the problems with having all this information and research is we can be overwhelmed by it. And it's great that we have this information — but know that kids can be incredibly resilient.”

When it comes to mental health, Ragan adds that “if you have any concerns at all that you may be feeling anxious or depressed — especially if you haven’t experienced that before — definitely tell your physician because they can tell you different strategies to cope with it. Early detection is the best kind of treatment.”

For More Information Contact

Writer: Audra Davidson

Communications Officer II, College of Sciences

Editor: Jess Hunt-Ralston

Director of Communications, College of Sciences