There’s a good reason why the Mars 2020 Mission Perseverance Rover and its mini-copter counterpart Ingenuity are currently busy exploring the edges of the Jezero Crater on the Red Planet. Water once flowed freely there, as it did eons ago at similar sites on Earth — and perhaps with it, water-deposited evidence of life deep beneath Jezero’s rust-colored boulders and sand.

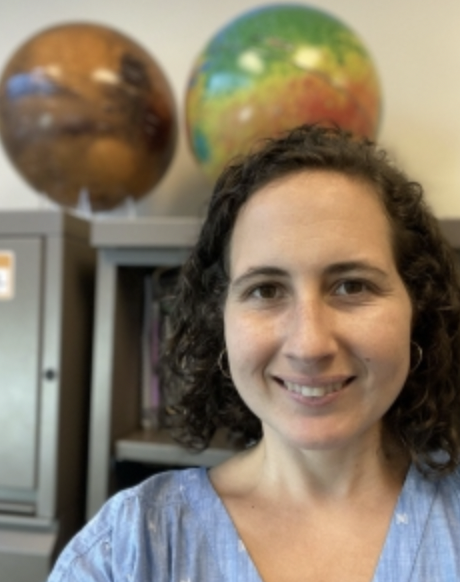

Those so-called terrestrial analog sites on Earth helped NASA choose Jezero for the mission. “Ancient lake beds are a major target for Mars exploration, as they provide evidence for sustained liquid water in Mars’ past — and lake muds commonly preserve biosignatures on Earth,” says Frances Rivera-Hernández, assistant professor in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. “Thus, if life ever persisted on early Mars, their past presence may be preserved in ancient lake beds.”

Rivera-Hernández, who joined Georgia Tech in January, will soon get a chance to study another analog site in the Antarctic, thanks to a four-year $700,000 NASA grant awarded to her research proposal, “Paleolake deposits in Miers Valley, Antarctica: An analog depositional record for Martian lakes through late Noachian to early Hesperian climatic transitions.”

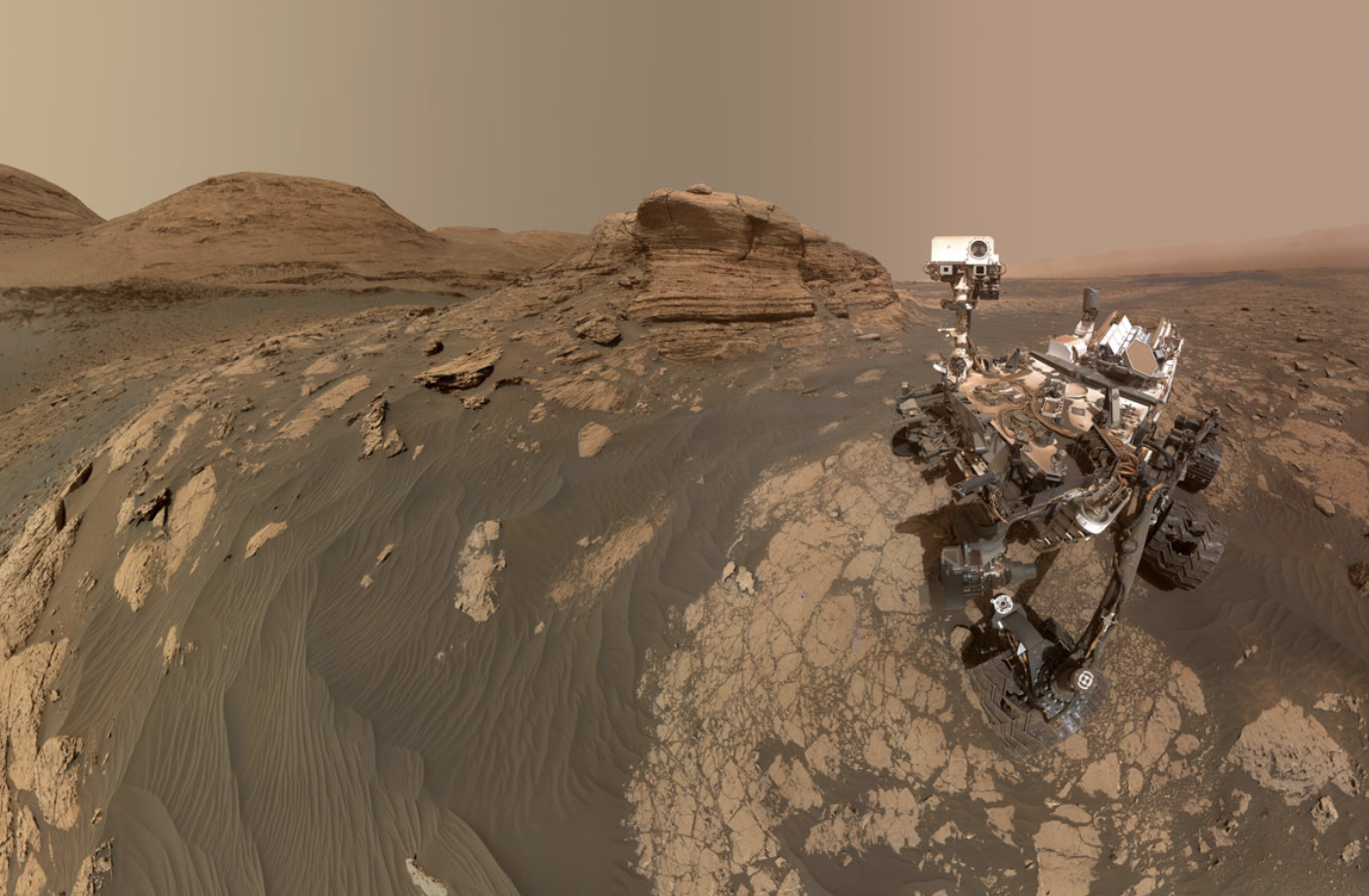

Just like the drilling and sampling now going on at Jezero Crater on Mars, Rivera-Hernández’s work may help NASA choose future Mars destinations for both robotic rover and crewed missions. That’s because Rivera-Hernández is also a collaborating scientist on NASA’s Curiosity Rover mission. “Lessons learned through the Antarctic project will help inform my work on the mission, as we have been characterizing lake bed deposits with the Rover,” she says. Since landing on Mars in 2012, Curiosity has traveled nearly 26 km (16.14 miles) around the rim of Gale Crater, another probable dry lake.

“I was ecstatic to hear that my grant was funded, and excited to be heading to Antarctica for field work,” says Rivera-Hernández, who will serve as the study’s principal investigator. Her co-investigator is Tyler Mackey, an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico. The grant will also provide funding for two graduate students, one from each institution. Field work is planned to start in January 2024.

“Before the field season, we will be performing remote sensing observations of our field site and performing lab-based analyses on modern lake samples to plan for the field work studying ancient lake beds,” Rivera-Hernández says.

Her lab team will study the deposits of a large Antarctic lake that persisted through climate changes 10,000 to 20,000 years ago to better recognize those similar changes in ancient lake beds on Mars, like those being explored by Curiosity and Perseverance.

“Currently, liquid water is not stable on the surface of Mars, but we have abundant geologic evidence for the presence of lakes on early Mars, suggesting that Mars’ climate was different in the past and that it changed through time,” Rivera-Hernández says. “But we still do not have a good understanding on whether this climatic transition was abrupt or gradual, or if Mars was significantly warmer when the lakes were present.”

That’s an unknown because lakes can form in a variety of climates, she adds. Examples are found in polar regions on Earth, where liquid water exists in lakes with permanent ice covers. “However, when ice is present in a lake, there are processes that are unique, and sometimes these produce deposits that may be recorded in lake beds. Thus, past climate may be inferred from lake beds if these unique deposits are recognized and distinguished from other deposit types.”

Rivera-Hernadez’s project will also help scientists recognize these unique deposits in ancient lake beds on Mars — by studying the deposits of that ancient Antarctic lake which experienced periods with and without an ice cover, due to those climatic changes on Earth.

For More Information Contact

Renay San Miguel

Communications Officer II/Science Writer

College of Sciences

404-894-5209