Editor's Note: This story was published originally by the Walter H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering on July 12, 2019. It has been slightly revised for the College of Sciences website.

When all of her classmates graduated from their Arts magnet high school in Baltimore and were moving on to study art on college campuses across the country, multi-talented Emily Madsen decided to do things a bit differently.

“I considered art school, too, because I really come from an artistic background. That’s what I was trained in,” says Madsen, whose favorite visual medium is oil paint, but who is also a musician. “But I wanted to be an engineer, because, you know, engineering is a very creative thing, too. And I’m also a very left-brained person. I like science and math. I’m a total nerd. I want to use those skills to help people. I have this need to try and solve problems and engineering fills that hole.”

In particular, biomedical engineering captured Madsen’s imagination, which is how she landed at the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University. But she hasn’t had to mothball her paint brushes and canvases or her viola, and her artist’s heart has thrived at Tech.

As a college student, Madsen has satisfied her music jones by playing in the Georgia Tech chamber orchestra. And for the past two years she has sated her passion for painting and visual art by creating a series of works designed to creatively interpret scientific research through a collaborative, student-run program based at Emory and Georgia Tech called Science.Art.Wonder. (or, S.A.W.).

Created to bring art together with science in an effort to spark discussion about complex scientific topics, S.A.W. matches college student artists with scientists to design works that effectively communicate the research, and the pieces are shared with the public – a fresh way of promoting science awareness and education that literally puts the A (Art) in STEAM (an approach to learning that uses Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Mathematics as access points for guiding a science-based, multidisciplinary student educational experience).

S.A.W. has – pardon the pun – gained steam since it was launched in 2018, with appointed student leaders from each campus and development of a new website. Madsen, who is entering her third year as a BME student, has been a part of the program from the beginning and has partnered with two different researchers from two different departments and one large interdisciplinary research institute, the Petit Institute for Bioengineering and Bioscience at Georgia Tech.

Visual Connections

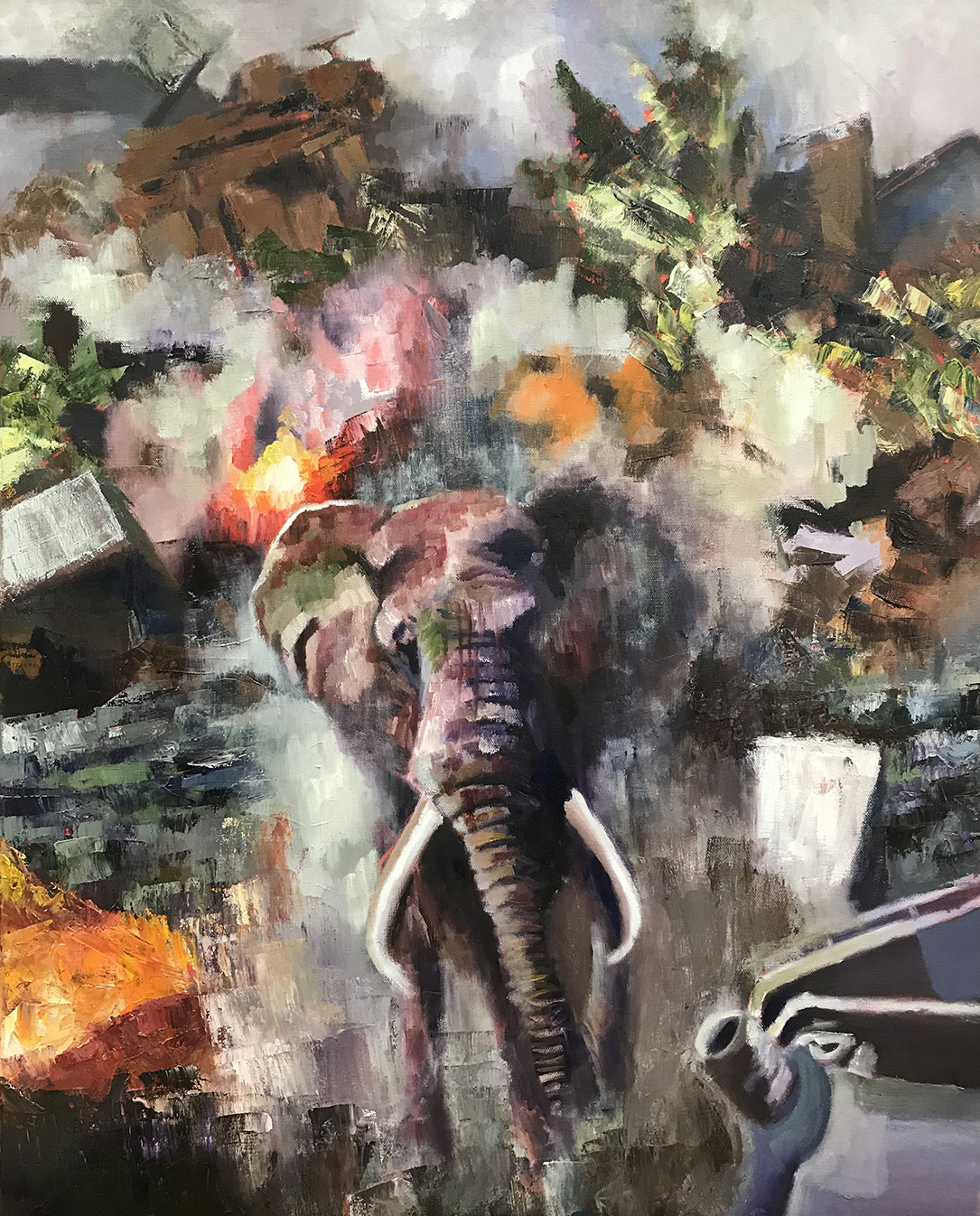

Last year she was partnered with Jianing Wu, a postdoctoral researcher from the lab of David Hu, associate professor of mechanical engineering and biological sciences and a Petit Institute researcher. Wu was studying the biomechanics of an elephant’s trunk, and applying that knowledge to the future development of prosthetic arms.

“They were hoping to develop tools for military situations, or disaster relief,” says Madsen, who has been spent the summer in Ireland as part of the BME Galway Summer Program (National University of Ireland/Galway). “For some reason, I thought instantly of war. There was a lot going through my mind and I had a difficult time processing it all. I wanted a message of hope – this mechanical arm that could go into disaster areas and help people.”

In one painting (“A New Era”), she considered the question of a world threatened by disaster and destruction, and whether elephant biomechanics would be part of the solution, presenting an image of abstract calamity surrounding a powerful, forward-facing elephant. In the other painting (“Second Nature”), the worlds of technology and nature are intertwined in an image of an elephant trunk evolving into a new device, her depiction of biology and engineering fused into one, a future in which humans respect, understand, and coexist with nature.

“In the process of creating the paintings, I used a lot of disaster imagery,” she said. “Oddly enough, while taking inspiration from that imagery, it brought me some peace of mind. How can this elephant painting and the associated research make me feel better about potentially horrible things like war and disaster? I was able to make a connection with other people, that’s how. And that was cathartic.”

Seeing the Whole Picture

This year, Madsen joined with Stephen Beckett, formerly a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Petit Institute researcher, Joshua Weitz, professor in the School of Biological Sciences and the School of Physics, and director of the Quantitative Biosciences (QBios) graduate program at Georgia Tech. Madsen is now a research scientist in the School of Biological Sciences.

Beckett investigates the role of the multitude of viruses in the ocean. There are about 50 million viruses per teaspoon of saltwater, and they are so plentiful that they could have a huge impact on phytoplankton, which is the base of the ocean food chain. On a global scale, phytoplankton also produce as much oxygen through photosynthesis as the trees of the world. In his studies, Beckett develops mathematical and computational models exploring the ecological interactions and dynamics of microbial communities.

“Viruses and the microbes they infect are the driving force behind Earth’s nutrient and energy transformations element cycling, and sustaining the planet’s biosphere,” Madsen explains. “Dr. Beckett and the Weitz group study the intimate relationship between marine viruses and how they shape ocean ecology.”

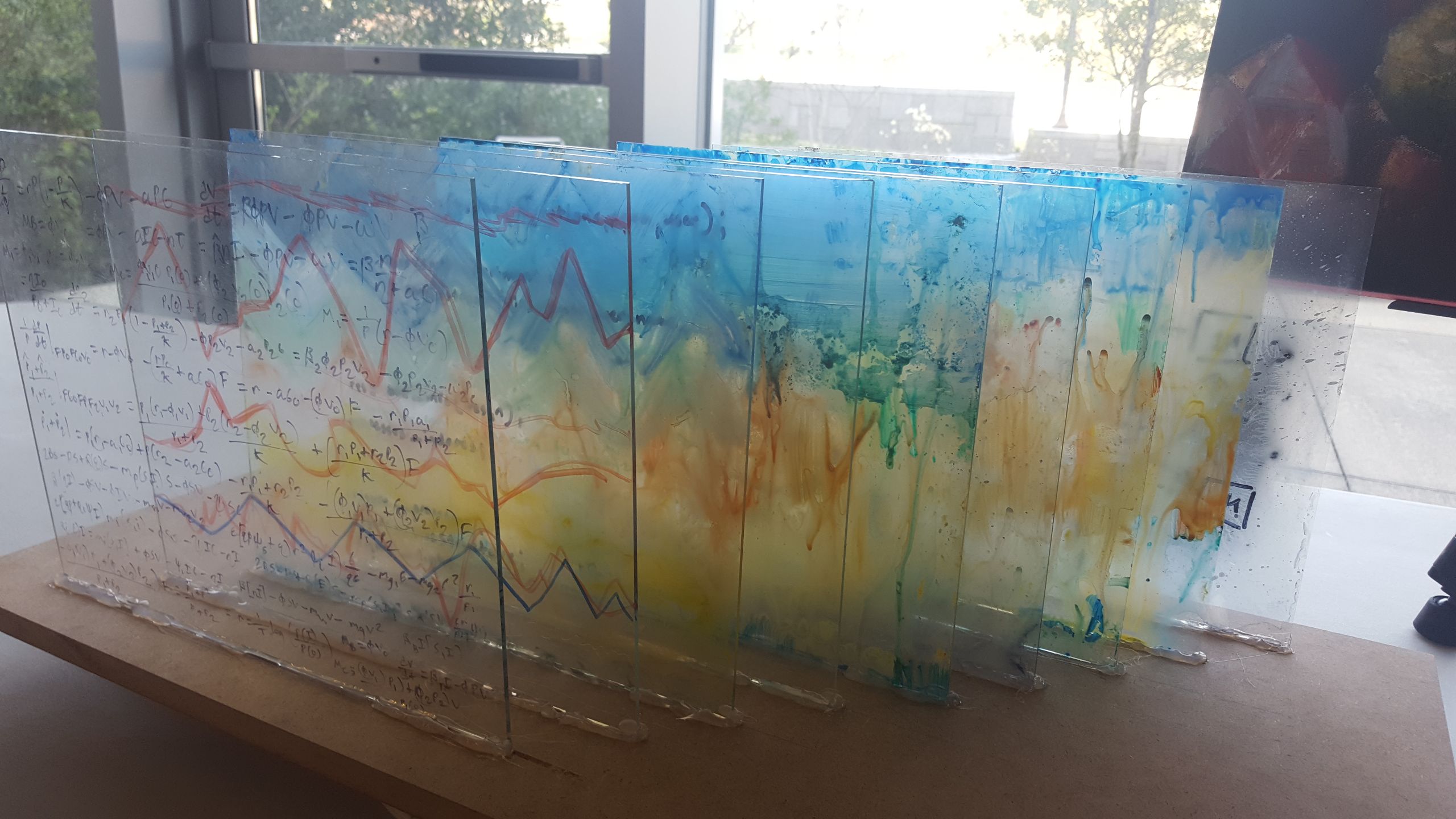

The result was two different pieces, “Submerged,” an oil painting, and “Through a Different Model,” a combination of glass, wood, and acrylic.

In the narrative she submitted for “Submerged,” Madsen wrote that the piece, “explores the complexity between marine viruses, their hosts and their vital role in shaping oceanic ecosystems. As science aims to discover the inner workings of the planet, art offers a visualization of our understanding of the world. Take it upon yourself to find connections between the microbes and the energy transformations, insert yourself into the microbial community and the range of ecosystems from the depths of the ocean floor to coral reefs to the thawing permafrost. Learn to anticipate the changing DNA of our planet, ponder what happens miles below the surface of the ocean, and for a moment, appreciate the small but vital impact these tiny microbes have on our planet.”

Regarding the three-dimensional work, she wrote, “the beauty of this concept lies in perceiving modelling as an artform. Both science and art aim to make sense of the multifaceted world around us. As an artist, I often find my intentions convoluted when creating a piece and figuring out how to best express the intricacies of my thoughts – this seems to parallel the process of mathematically modelling viral interactions. How can we illustrate something that cannot be currently visualized? Sometimes we need to focus on a single layer; a line of code, a formula, a pattern, a color, a line. Sometimes we need to observe through a microscope, other times we need to put down the paint brush and see the ‘whole picture’ and then adjust the details. Often we uncover beautiful relationships hidden in a sea of calculations, colors, and ideas. Hopefully, our end result is an illustration of the intangible, an understanding of the convoluted, and a contribution to something larger than ourselves.”

Beckett says the sculpture, “really explores how various types of abstractions can make us think and feel differently about our observations. For me, it really captures some of the key steps in the scientific process.”

Embracing the Process

For Madsen, it’s always been about the process, particularly with her art. More than the final results, she finds her bliss in the act of doing and making.

“I’m a process artist,” she says. “As much as I care about the final painting or the final sculpture, I care more about the process, the art of laying the paint down and making decisions. In high school we were trained in all mediums, but were allowed to focus on one that really spoke to us. I didn’t start painting until my sophomore year, but I fell in love with it. With working the paint – oil paint is very thick. It’s got a great texture, and there’s a lot of depth to it. I’m also a color person. I love color. So I really love feeling the paint, mixing it, working it, responding to it. That’s definitely my medium.”

It’s that same love of the process that is liable to make her a successful biomedical engineer, fully engaged in the development of the device or product.

“As an engineer, of course you want a great final result, but you’re constantly challenging yourself until you get there,” she says. “As an artist, one decision during the process affects subsequent decisions. It’s the same in engineering. So, being a process-focused person will help me in that regard.”

Madsen isn’t pursuing a career in art because she wants to preserve her painting and sculpting as labors of love. She does the art for herself without worrying about the outcome – although, making a connection is important to her. That’s part of why she got into biomedical engineering.

“Why is there so much heart disease in Africa? It’s because people there don’t have access to the same stuff that we do, and I’m really troubled by that,” she says. “As much as I love all the technological innovation in the world and all around me, my main aspiration now is to pursue research and development on medical devices to make them more accessible and affordable for lower income people and communities around the world. I think that I can help people as a biomedical engineer. Like my art, it’s a way to connect with people. That’s what I want to do.”

For More Information Contact

Jerry Grillo

Communications Officer II

Parker H. Petit Institute for

Bioengineering and Bioscience