As the Covid-19 pandemic raged, news reports show that sales of electronic air cleaners have surged due to concerns about airborne disease transmission. But a research team at the Georgia Institute of Technology has found that the benefits to indoor air quality of one type of purifying system can be offset by the generation of other pollutants that are harmful to health.

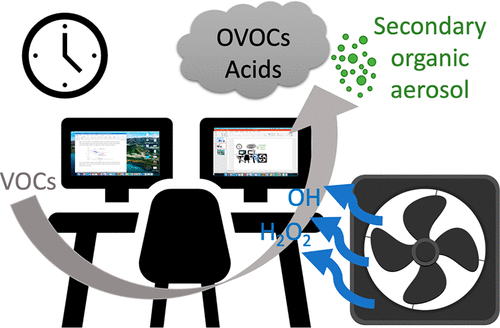

Led by Associate Professor Nga Lee “Sally” Ng in Georgia Tech’s School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering and the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, the team evaluated the effect of a hydroxyl radical generator in an office setting. Hydroxyl radicals react with odors and pollutants, decomposing them, and hydroxyl radical generators have been marketed to inactivate pathogens such as coronaviruses.

However, Ng’s study found that in the process of cleaning the air, the hydroxyl radicals generated by the device reacted with volatile organic compounds present in the indoor space. This led to chemical reactions that quickly formed organic acids and secondary organic aerosols that can cause health problems. Secondary organic aerosols is a major component of PM2.5 (particulate matter with a diameter smaller than 2.5 mm), and exposure to PM2.5 has been associated with cardiopulmonary diseases and millions of deaths per year.

The paper, “Formation of oxidized gases and secondary organic aerosol from a commercial oxidant-generating electronic air cleaner,” is published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology Letters.

While the pandemic has made various types of electronic cleaners increasingly popular, Ng explained that consumers are probably not aware of the secondary chemistry taking place in the air, with the pollutants generated not being directly emitted by the cleaning device itself.

“There are increasing concerns regarding the use of electronic air cleaners as these devices can potentially generate unintended byproducts via oxidation chemistry similar to that in the atmosphere,” Ng said.

Two types of air cleaning technologies are commonly used to remove indoor pollutants such as particles or volatile organic compounds and to inactivate pathogens: mechanical filtration and electronic air cleaners that generate ions, reactive species, or other chemical products such as photocatalytic oxidation, plasma, and oxidant-generating equipment (e.g., ozone, hydroxyl radical), among others.

Ng’s team selected a hydroxyl generator for the study to measure the oxygenated volatile organic compounds and the chemical composition of particles generated by the device in an office on the Georgia Tech campus.

While previous research reported pollutant formation from various electronic air cleaners (ionizers, plasma systems, photocatalytic systems with ultraviolet lamps, etc.), Ng believes that her team’s study is the first to monitor the chemical composition of secondary pollutants in both gas and particle phases during the operation of an electronic device that dissipates oxidants in a real-world setting.

Advanced instrumentation made Ng’s study possible. Gas-phase organic compounds were measured using a high-resolution time-of-flight chemical ionization mass spectrometer, purchased through a National Science Foundation major instrumentation grant. The study received support from Georgia Tech’s Covid-19 Rapid Response fund.

Ng noted that future studies on air cleaning technology should not be limited to inactivation of viruses or reduction of volatile organic compounds, but should also evaluate potential oxidation chemistry and the formation of unintended harmful gaseous and particulate chemicals.

“More studies need to be conducted on the effects of these devices in a variety of environments,” Ng said. “Electronic air cleaners greatly rose in prominence because of the pandemic, and now there are a lot of these devices out there. Millions of dollars are being spent on these devices by businesses and schools. The market is huge.

“Our results show that care must be taken when choosing an adequate and appropriate air cleaning technology for a particular environment and task,” she said.

Ng stressed the importance of future studies concerning the unintended effects of electronic purifiers, as these devices are not currently well regulated and do not have testing standards.

“There needs to be more peer-reviewed scientific data on electronic air cleaners,” Ng said. “We hope that additional studies will lead to more government guidelines and regulation.”

CITATION: Joo et al., “Formation of oxidized gases and secondary organic aerosol from a commercial oxidant-generating electronic air cleaner.” (Environmental Science & Technology Letters) https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.estlett.1c00416

About the Georgia Institute of Technology

The Georgia Institute of Technology, or Georgia Tech, is a top 10 public research university developing leaders who advance technology and improve the human condition.

The Institute offers business, computing, design, engineering, liberal arts, and sciences degrees. Its nearly 40,000 students representing 50 states and 149 countries, study at the main campus in Atlanta, at campuses in France and China, and through distance and online learning.

As a leading technological university, Georgia Tech is an engine of economic development for Georgia, the Southeast, and the nation, conducting more than $1 billion in research annually for government, industry, and society.

Media Relations Contacts: Jason Maderer (jmaderer3@gatech.edu) or Brad Dixon (braddixon@gatech.edu).

Writer: Brad Dixon

For More Information Contact

Jason Maderer, jmaderer3@gatech.edu