Editor's Note: This story by Melissa Fralick originally appeared as part of the special feature "Campus Without Borders," in the Spring 2018 Issue of Georgia Tech's Alumni Magazine.

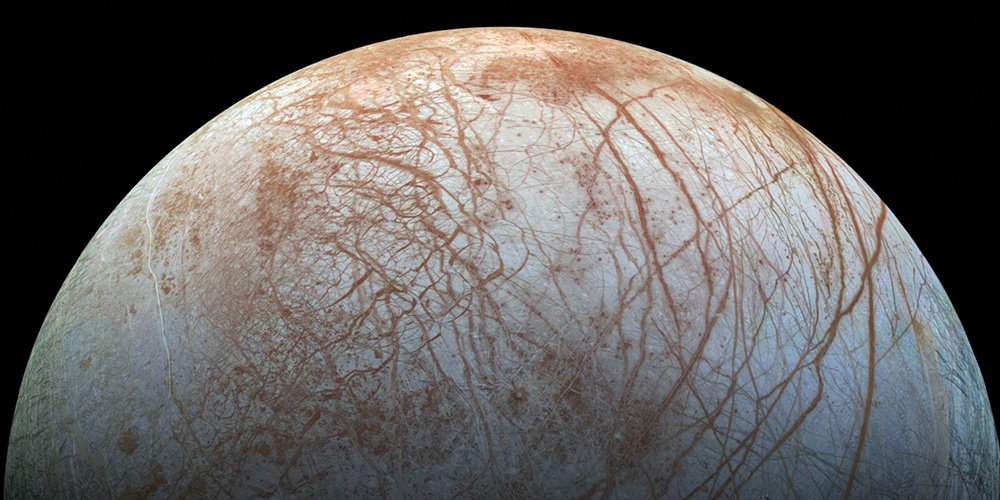

IF THERE IS LIFE ANYWHERE ELSE IN OUR SOLAR SYSTEM, Britney Schmidt knows it’s likely to be found on Europa, one of Jupiter’s largest moons.

Europa has a lot in common with our planet. Like the Earth, it has an iron core, a rocky mantle, and a salt water ocean—though Europa’s ocean is encased under an ice shell up to 15 miles thick.

But as of yet, no spacecraft has explored beneath the icy surface.

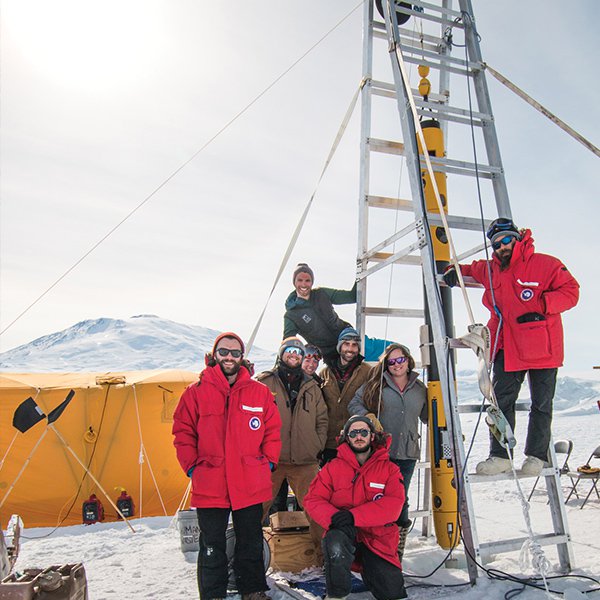

Schmidt, who is an assistant professor in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, hopes to change that. She and her team of Tech students and researchers are testing a modular autonomous vehicle, called Icefin, which they hope will one day lead to driving vehicles under Europa’s ice.

But before they’re able to launch Icefin into space and land on Europa, they’re working here on Earth’s iciest region: Antarctica. Antarctica provides the perfect environment for testing, because it mimics many of the conditions expected to be found on Europa.

Vast ice shelves? Check. A deep, salty ocean below? Check. Challenging to navigate? Check.

“Astronauts go out and learn geology on Earth before they go to the moon or before they’ll go operate on Mars,” Schmidt says. “So that’s kind of what we’re doing here— a spacecraft mission under the ice before we go and attempt that on Europa.”

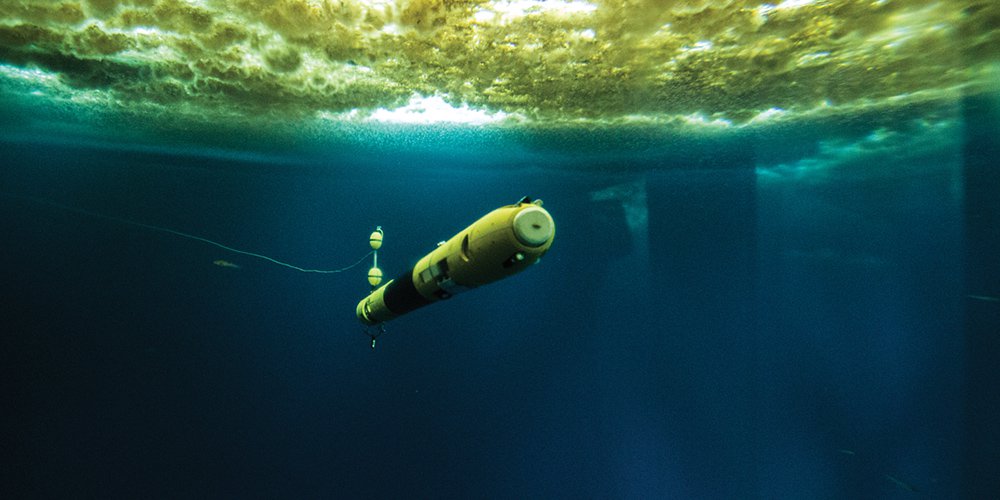

Schmidt and a team of researchers, including graduate students Justin Lawrence, Dan Dichek, Ben Hurwitz and Chad Ramey, along with research engineer Matt Meister, ME 15, returned to campus this January following a three-month field season, during which they successfully operated a new version of Icefin under Antarctica’s McMurdo Ice Shelf for the first time. The missile-shaped vehicle, which is 12 feet in length and 9 inches in diameter, was designed to be small and modular enough to transport onto remote ice shelves, but sophisticated enough to carry a variety of scientific instruments and sensors. It can be driven under the ice remotely, like a remote-controlled car, or programmed to drive autonomously.

The team includes students from various disciplines who bring their expertise to the project. For example, Lawrence is working toward a PhD in planetary science, while Hurwitz is part of a new PhD program at Tech in ocean sciences and engineering.

“The engineers and scientists work really closely, which is fantastic for field work,” Lawrence says.

Before their recent fieldwork with Icefin, all scientific data from the massive Ross Ice Shelf, which is roughly the size of France, came from just three drill holes.

“We know more about the surface of Mars than we do about under the Ross Ice Shelf,” Hurwitz says.

Schmidt says that over the course of this Icefin project—a collaboration with a New Zealand research team—exploring through three additional holes drilled into the Ross Ice Shelf will more than double the data previously available.

“And with the vehicle, it’s a type of data that we’ve never been able to get, which is driving around and mapping what’s going on under there for a few kilometers on either side of the access point,” Schmidt says.

While their field work in Antarctica serves as a dry run for a future mission to Europa, Schmidt and her students are also advancing science here on Earth by exploring uncharted territory deep under the ice.

“Antarctica is the most beautiful, most inspiring, and hardest place to work that I have ever been. You just feel so small and insignificant and like you’re so lucky to be there in that minute. And I imagine that’s what it would be like if you were standing on the surface of Europa.”

“This field season was spectacularly successful from an engineering standpoint,” Hurwitz says. “But we also got much more science data than we could have expected.”

During their recent trip, Icefin’s footage revealed a surprising diversity of life deep under the ice , Schmidt says. A seal bumped into the vehicle at a depth of 200 to 250 meters. The craft also encountered a rare, giant Antarctic fish called a toothfish.

Icefin was able to travel to the sea floor at a depth of almost 800 meters. Plus, the team was able to navigate the vehicle under a rift in the ice shelf and discovered ice caves that were likely formed by cold water flowing down the rift.

“Much of what we saw this time around no one has ever seen before,” Schmidt says. “It’s cool because the vehicle has gone deeper than, as far as we know, any other vehicle in the area has ever gone and way deeper than divers can go. So all this work is really, really new.”

Lawrence, who’s been working with Schmidt since 2015, was excited to view the ocean floor.

“It was incredible to see it for the first time with a vehicle that we built,” he says.

This was Schmidt’s fifth season in Antarctica, and she’s already planning next year’s trip, when the team will focus on Icefin’s automated process and gathering much more science data. She refers to the trips as seasons, because the team typically spends around three months each year in the field during the Antarctic spring and summer.

“It’s a weird way to live,” she says. “You’re spending a quarter of your life down there, and then you’re spending the other three quarters of it planning to be down there. I’m always in the field, whether it’s physical or mental.”

Schmidt’s graduate students say they feel fortunate to be part of such groundbreaking research.

“It’s not a common thing and I’m grateful for the opportunity. I’m thankful that there is so much support for this kind of work,” Lawrence says.

Humans may never step foot on the surface of Europa, and an unmanned mission to the icy moon likely won’t happen for another few decades. But until then, Schmidt says she feels lucky to be able to spend her time working in Antarctica to advance the search for life in the cosmos.

“Antarctica is the most beautiful, most inspiring, and hardest place to work that I have ever been,” Schmidt says. “You just feel so small and insignificant and like you’re so lucky to be there in that minute. That is how I feel every day that I walk out there. And I imagine that’s what it would be like if you were standing on the surface of Europa.”

For More Information Contact

A. Maureen Rouhi, Ph.D.

Director of Communications

College of Sciences