Peter Addison’s schedule for the coming school year is already on a par with students who have been in a Ph.D. program for two or three years. In December he will head to the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union, the largest gathering of planetary and space scientists in the world. He’s also on track to make a presentation at an international conference on space science in Japan in September 2021.

Which makes the fact that Addison is about to receive his undergraduate degree from the School of Physics, graduating with highest honors, all the more remarkable.

“Normally our Ph.D. students start attending (the AGU meeting) at the end of their second or third years,” says Sven Simon, associate professor in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences and Addison’s research group director. “But given Peter’s exceptional skills as a researcher, I am convinced that he will do an outstanding job there.”

After Simon’s research group on planetary plasma environments won a major research grant from NASA’s Solar System Workings program, “it was already abundantly clear that we wanted Peter to join this project as a Ph.D. student,” he says.

For Addison, a recipient of the prestigious President’s Fellowship for incoming graduate students, it’s all part of the Georgia Tech experience. “Georgia Tech has taught me the meaning of hard work. Nothing comes to you for free here,” he says. “The School of Physics is filled with some of the most intelligent men and women I have ever met, far smarter than me, and it’s been a privilege to learn how our world works from them. That being said, I never want to do quantum mechanics ever again.”

A different kind of physics

Addison has been more interested in theoretical plasma physics, especially that of magnetospheres in the outer solar system. After meeting with Simon In late 2018, he joined Magnetospheres of the Outer Solar System, the research group Simon directs. He said Addison had already received a good background in theoretical astrophysics, thanks to taking Tamara Bogdanović’s classes through the Center for Relativistic Astrophysics.

“When Peter and I talked for the first time, we decided that he would join my group as a teaching assistant,” says Simon. “At that time, I was looking for a TA for my spring 2019 class on ‘Mathematical Methods in Geophysics.’ This is actually a graduate-level class that covers advanced mathematical concepts. Although he was still an undergraduate student at that time, I had no doubt that Peter’s excellent background in theoretical physics would make it easy for him to handle this challenging task. During the next couple of months, he proved to be an extraordinarily dedicated and reliable group member as well as a great teacher, proactively rendering support to the students whenever needed.”

Plotting possible paths for NASA’s Europa Clipper

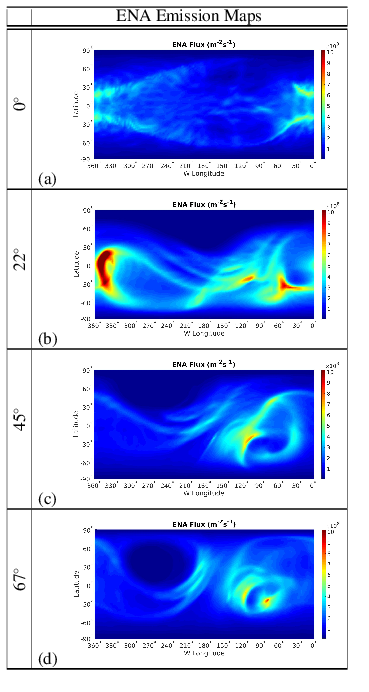

Addison’s own research deals with the ultimate goals of NASA’s forthcoming Europa Clipper mission. He is developing a new model of the interaction between Europa, Jupiter’s intriguing moon which is a good candidate for harboring potential life, and Jupiter’s planetary radiation.

“Our group tries to understand how the moons of planets like Jupiter and Saturn interact with their parent planet’s environment, specifically via magnetic field interactions,” Addison says. Moons like Europa and Saturn’s Titan orbit within the magnetosphere of their parent planets, and they receive constant bombardment of high energy particles.

Understanding which regions of the moon receive the highest levels of irradiation can help explain surface features, the existence of atmospheres, and even help decide where and how to land and protect probes that NASA may send to these moons to explore.

Addison‘s research, based on an earlier tool developed by former group postdoctoral researcher Lucas Liuzzo, involves generating surface irradiation maps for Europa. It’s something Addison’s done “from scratch – a completely new simulation model that will calculate the irradiation of Europa,” Simon says. The goal is to reveal signs of possible life that haven’t been bombarded into oblivion by the harsh radiation. Those areas could be prime landings sites of NASA’s Europa Clipper probe. Simon adds, “Peter makes progress on this project at a remarkable rate, coming up with new procedures and ideas for his model every week.”

In fall 2021, Addison will present the latest findings on his research at the 14th International School/Symposium for Space Simulations in Kobe, Japan. “It’s a privilege to present our science to the some of the best scientists in the world. However, I’m also there to learn,” Addison says. “It’s not often that you gather many of the great minds of space sciences in one place, and it will be a tremendous opportunity to see what research everyone else is cooking up.”

For More Information Contact

Renay San Miguel

Communications Officer

College of Sciences

404-894-5209