Georgia Tech’s Colleges of Sciences and Engineering have long collaborated to launch successful joint space science research projects with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Researchers across both Colleges and the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) are now hard at work on several ambitious projects related to NASA’s planned return to Earth’s moon — and beyond.

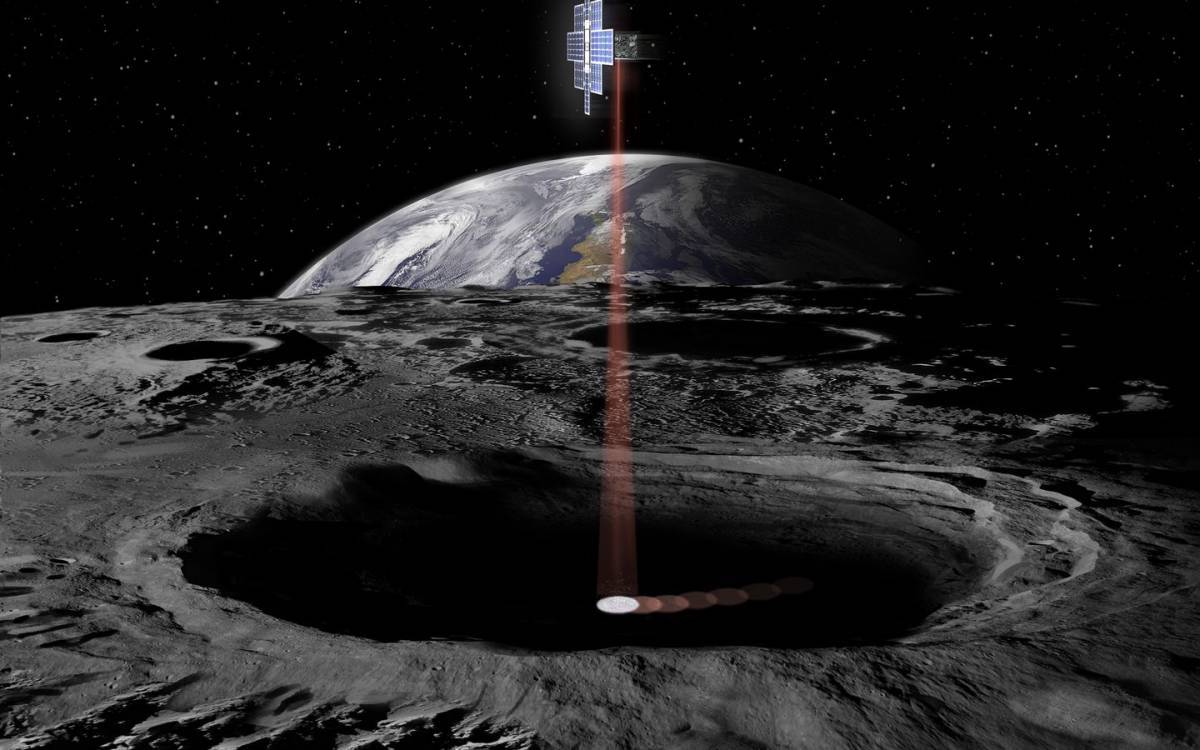

Lunar Flashlight to Search for Ice on the Moon

Thomas Orlando says NASA is always looking for multidisciplinary research programs at the higher education level. He uses a recent win of a key NASA partnership, dubbed the Lunar Flashlight Mission, as an example of what’s been a very successful approach for the Institute.

Orlando is a professor in the School of Chemistry and Biochemistry, principal investigator for NASA REVEALS (Radiation Effects on Volatiles and Exploration of Asteroids and Lunar Surfaces), and former co-founder and director of Georgia Tech’s Center for Space Technology and Research (C-STAR.)

REVEALS is researching ways to prepare NASA for the next generation of its crewed space missions, and is, itself, part of a larger NASA program, SSERVI (Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute).

The project includes designing spacesuits with radiation detection materials sewn into the suits — and using the Moon’s natural resources (buried ice for water, minerals at or near the surface) to support astronaut habitats. That ice could also provide drinking water for astronauts and possibly help fuel engines built on site.

“REVEALS is focusing on the water on the Moon issue. This involves understanding how it is made or delivered, how it is transported, and where it is. The work also involves developing technologies to extract it, a project lead by Peter Loutzenhiser (George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering). We obviously need to know how much is there and whether we can get it and utilize it. This is where Lunar Flashlight comes in,” Orlando says.

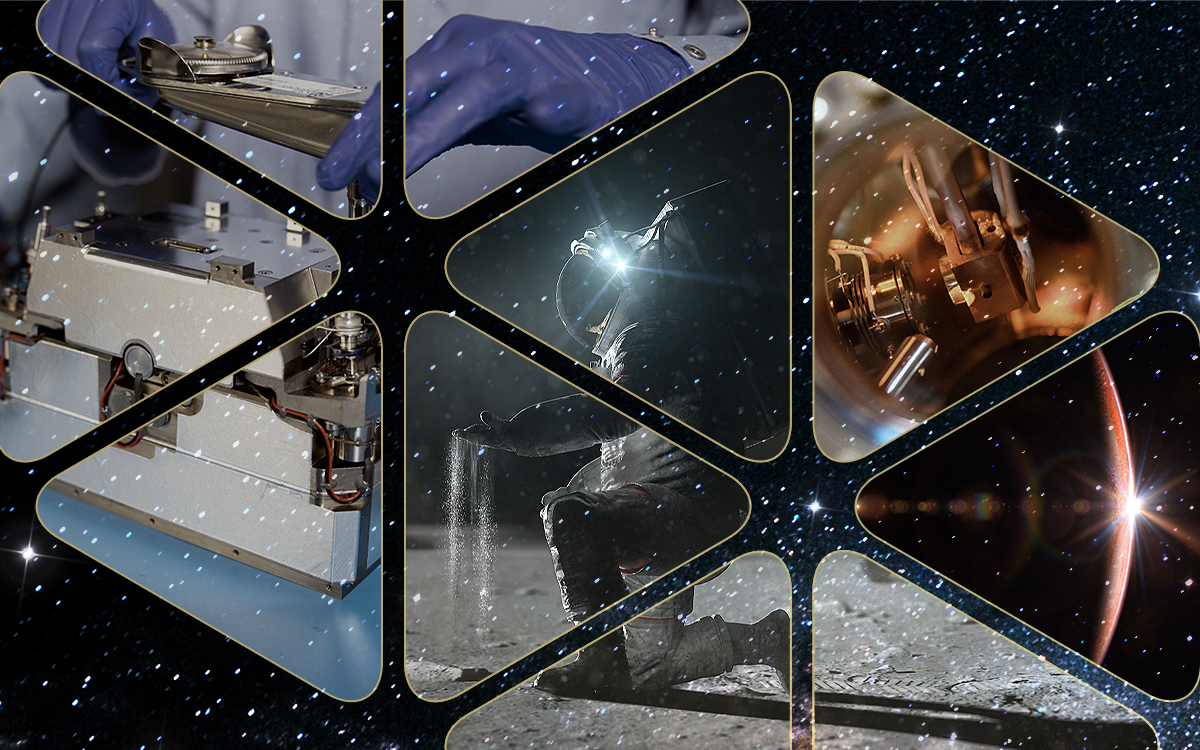

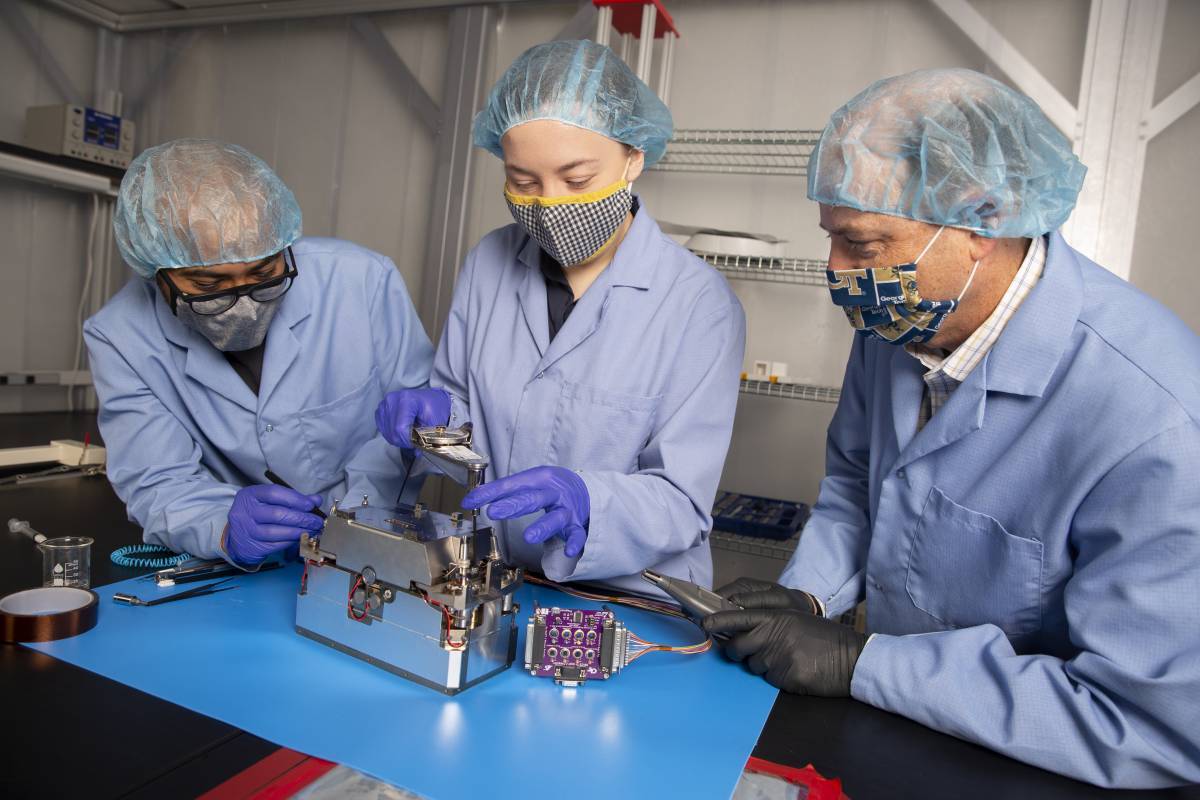

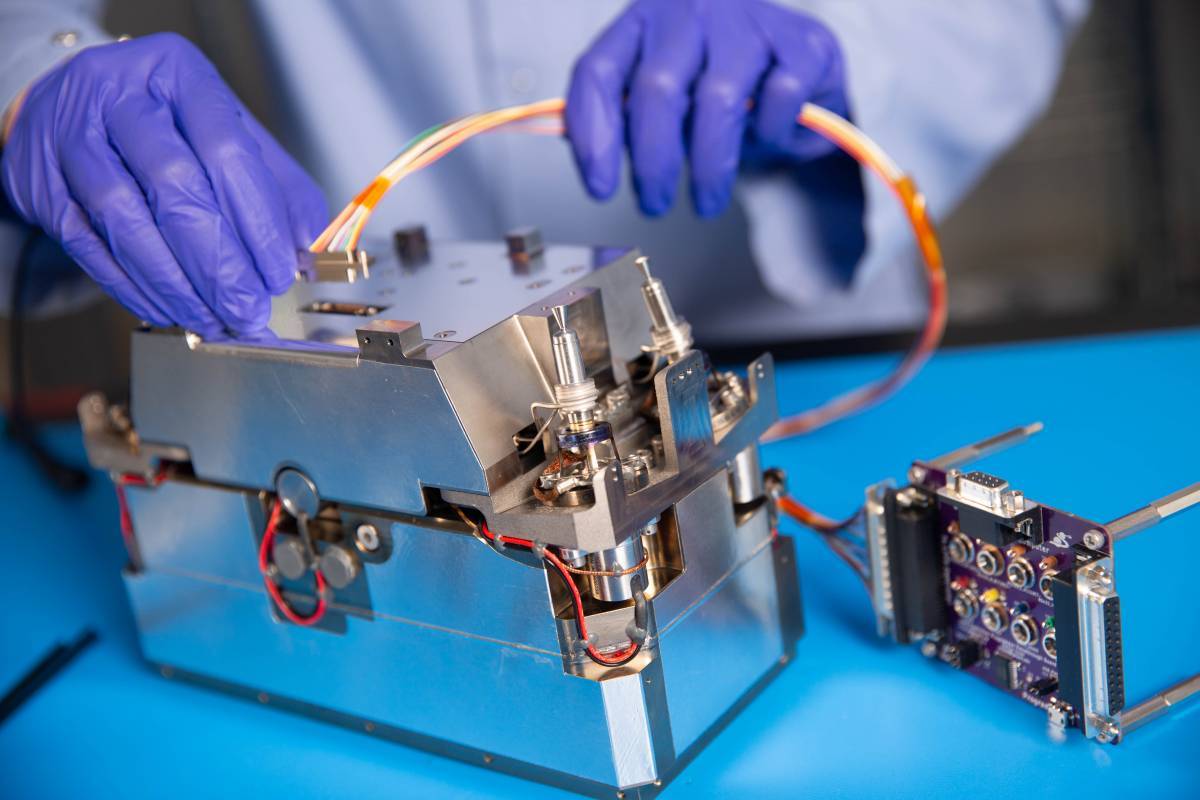

The Lunar Flashlight project also focuses on deep collaboration and coordination across several agencies and teams. This past summer, the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California shipped all spacecraft parts to Tech's Atlanta campus to begin assembly and testing. GTRI is now providing the clean room for assembly, and a team of researchers, led by Jud Ready, is managing all the integration and testing of Lunar Flashlight before it is shipped to the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for fueling, then on to Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida, for launch in 2022.

“Our new Center for Space Hardware Assembly, Fabrication and Testing will provide the cleanroom space to assemble Lunar Flashlight and put it through a rigorous series of tests,” says Ready, who is principal investigator of the Lunar Flashlight project. Ready also serves as deputy director of Innovation Initiatives for the Georgia Tech Institute for Materials (IMat), is an adjunct professor in the School of Materials Science and Engineering, and is a principal research engineer at GTRI.

“There’s no instruction manual right now — it’s our role to collaborate with the scientists and engineers at JPL and the other partners to write the test and integration procedures, do them, and at the same time to conclusively verify our work,” Ready says.

Tiny CubeSats Take to the Sky

The Lunar Flashlight is a CubeSat — a mini-satellite that’s basically what its name implies: a 6U CubeSat (30 x 20 x 10cm), about the size of a desktop tower computer. CubeSats can weigh anywhere from 3 to 20 pounds, and can be deployed much easier and at a lower cost than traditional satellites.

Since their introduction in 1999, CubeSats have become popular for science and commercial satellite deployment, while allowing Engineering and Sciences students at schools such as Georgia Tech to design and deploy their own satellites.

“That’s great in and of itself, for our students to have an opportunity to build a satellite and send it into space,” Glenn Lightsey, David Lewis Professor of Space Systems Technology in the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering, and current C-STAR director, says. “They can apply to a company with a resume that says, ‘I’ve already built a satellite and it’s in space talking to others.’ Twenty years ago, that just didn’t happen.”

Lunar Flashlight CubeSat will have sensitive instrumentation for locating buried ice on the Moon, and Lightsey’s team has already built its propulsion system. After launch from Kennedy Space Center, Lunar Flashlight will have its mission control operations run out of Lightsey’s lab.

Engineering hardware with scientific instrumentation — Lightsey says you can’t illustrate Georgia Tech’s strengths as a NASA partner any better than with interdisciplinary projects like the Lunar Flashlight.

“I think Georgia Tech has a competitive advantage based on how it is really emphasizing interdisciplinary research from the beginning, from idea generation on. There aren’t many institutions like it in my opinion. It’s in Georgia Tech’s bones.”

Lunar Dust-Busting in NASA’s BIG Ideas Challenge

The REVEALS program is also looking at ways to wipe out the problem of lunar dust, which can have an inherent electrical charge and can be more damaging to equipment than Earth dust. It can also be a health hazard if it sneaks into an astronaut’s habitat.

“It’s an engineering project, but a science problem,” Orlando says. “Here’s an example of where engineering and science got together, and something great came out of it.”

NASA’s BIG (Breakthrough, Innovative, and Game-Changing) Ideas Challenge, a competition for undergraduates and graduate students to brainstorm away problems for the space agency, was dedicated to lunar dust mitigation for the 2021 version. That project is led by Julie Linsey, a professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering who is mentored by Orlando and Lightsey, along with REVEALS research scientists Micah Schaible and Zach Seibers, a student team of engineering students — Varun Bose, John Fitton, Zhen Liu, Dicky Silitonga, Kristoffer (Kris) Sjolund, and Jeffery Zhang. The crew came up with a hybrid brush, which uses both an electrodynamic system (EDS) and ultraviolet (UV) technology to keep dust from building up on lunar spacesuits.

The team, which called itself Shoot For the Moon, is among six BIG Ideas Challenge finalists. Shoot For the Moon will give a presentation on the hybrid brush at the BIG Ideas Forum in November.

Two members of the REVEALS team also recently presented their work on human space exploration. Faris Almatouq, a graduate student in the School of Physics working on novel radiation detectors, and Kris Sjolund, a graduate research assistant in mechanical engineering working on the dust brush, both won first prize in the poster contest at the SSERVI/NASA Exploration Science Forum and European Lunar Workshop in July.

“These students and co-investigators are all doing great and impactful work,” Orlando says. “There’s an interesting distribution of students working on BIG Ideas projects. They’re mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, and aerospace engineering students. And there were chemists and other scientists advising them. It was a multidisciplinary student team — and a multidisciplinary advisory team.”

From our State to our Solar System

Orlando and Lightsey also note that Tech’s graduates are already finding jobs with Blue Origin and SpaceX, two of the new commercial space businesses with successful crewed maiden flights earlier in the summer. That’s in addition to how Georgia Tech has seeded NASA and JPL, plus Lockheed, Boeing, and other established aerospace companies, with former students.

“Almost half of my students are getting a graduate degree in engineering and a graduate degree in science,” Orlando says. “They typically get a master’s in engineering or materials science and a Ph.D. in chemistry or physics. It markets them much more for SpaceX or NASA. It’s this hybrid training that people are looking for, and I can’t think of a better place for it than Georgia Tech.”

Lightsey and Orlando hope to one day welcome nearby universities, such as Emory University and the University of Georgia, as partners in some of these initiatives. The move would combine resources and expertise from all three institutions to create a first-of-its-kind statewide space science initiative or institute in Georgia.

That kind of collaboration could also help create a new powerhouse for planetary and space science research close to home research institutions — and could help create more job opportunities to retain Georgia talent, with young alumni working in a range of aerospace-related industries with freshly minted Georgia-grown degrees in hand.

“There’s a lot of interest,” Lightsey says. “Who doesn’t want to work on space exploration? This is something that resonates with everyone in every discipline. I think all the institutions have different areas of expertise they can contribute. I think collectively we can be much more complete than just one institution by itself.”

World Space Week 2021: Georgia Tech to Host Space Day Atlanta

The Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering at Georgia Tech will host Space Day Atlanta on October 9, 2021as an effort to launch local K-12 students’ interest in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

The day-long event on campus, organized by NASA’s Georgia Space Grant Consortium (GSGC), will allow local schoolchildren to see demonstrations of current aerospace research at Georgia Tech, as well as participate in various hands-on activities such as virtual flights to Mars and rocket building and launching. Learn more.

For More Information Contact

Renay San Miguel

Communications Officer II/Science Writer

College of Sciences

404-894-5209