Download this episode

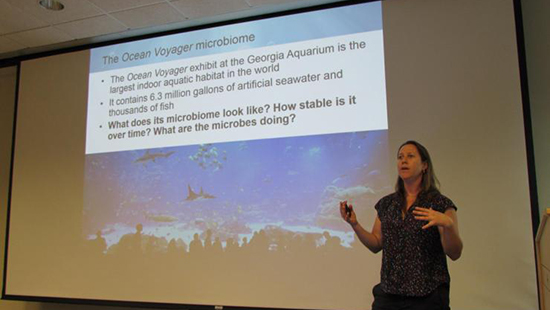

Massive whale sharks headline the Ocean Voyager exhibit at the Georgia Aquarium. Its tiniest residents are the ones that concern Nastassia Patin. The School of Biological Sciences postdoctoral researcher studies the exhibit's microbiome, and what she’s learning may help keep all aquariums clear and healthy.[Upbeat music]

- Renay San Miguel:

-

Hello, I’m Renay San Miguel and this is ScienceMatters, the podcast of the Georgia Tech College of Sciences. Aquarium visitor: I love aquariums!

Renay San Miguel:

Renay San Miguel:-

Welcome to Ocean Voyager, the largest exhibit at one of the largest aquariums in the world — the Georgia Aquarium.

- Aquarium visitor:

-

Who’s the turtle?

- Aquarium docent:

-

His name is Tank.

- Aquarium visitor:

-

Hi Tank!

- Renay San Miguel:

-

You’ll find Tank the sea turtle in the Ocean Voyager exhibit, plus whale sharks, manta rays, hammerheads, and most of the aquarium’s larger animals. Joe Handy, Georgia Aquarium President/COO: Part of our history is doing big things. Building an aquarium in a landlocked city was big. Building an Ocean Voyager gallery was big.

- Renay San Miguel:

-

That’s Joe Handy, Aquarium president and chief operating officer, from a video detailing expansion plans for the facility. While the Georgia Aquarium is getting larger, providing more dorsal fin room for its biggest fish, a Georgia Tech researcher is more concerned with its much smaller residents, and how they impact the overall health of the exhibit.

Nastassia Patin:

Nastassia Patin:-

We were interested in the bacteria and the other microorganisms that lived in the water of the aquarium.

- Renay San Miguel:

-

Nastassia Patin is a postdoctoral researcher in the School of Biological Sciences. She studied Ocean Voyager’s water with two other researchers from that school: principal investigator Frank Stewart, an associate professor, and postdoctoral fellow Zoe Bratte.

- Nastassia Patin:

-

These microorganisms are real important in terms of breaking down waste products and cycling nutrients, but in terms of the specific players of who was there and who was doing what, that was completely unknown, so we wanted to go in and look at that.

- Renay San Miguel:

-

For 14 months, her team worked with Aquarium scientists to sample the salt water in Ocean Voyager. They then spent four months using the latest genetic technologies to analyze the samples. They want to know if a 6-point-3 million-gallon artificial tank housing thousands of fish species in the middle of downtown Atlanta comes close to the natural habitats you’ll find in the middle of an ocean. Patin joined me at the Georgia Aquarium for a late spring morning interview. We began as school tour groups started to file through the exhibits. Your research was titled, ‘Microbiome dynamics in a large artificial seawater aquarium.’ So what is a microbiome?

- Nastassia Patin:

-

A microbiome is a community of bacteria and other microorganisms that are associated with every environment on Earth. So every animal and every ecosystem like the ocean or soil has its own unique community of microorganisms, and we know the most about the human microbiome, the bacteria and organisms that live in our guts and are really important for our health. And we’re starting to learn more about the microbiomes of other environments like the ocean, but in terms of microbiomes that live in man-made or artificial environments, that’s really a new frontier.

- Renay San Miguel:

-

And why is that? It seems to me that we’ve been building aquariums for a long, long time all over the world. Aquariums big and aquariums small. And we still don’t know the answer to that question of whether microbial communities in artificial environments can be anything like the ones we find in the wild?

- Nastassia Patin:

-

Well, microbiome science in general is a very new field, we’ve only had the DNA-sequencing technology for the last 10 to 15 years to fully understand the complexity of these systems. And we really need that technology because most bacteria in the environment can’t be grown in the lab. We don’t know how to grow them. Most estimates say over 99 percent of the bacteria can’t be grown in petri plates in the lab, and so the way we study them is to go directly to the environment and sequence their DNA and try to understand from their genes who they are and what they’re doing. [Aquarium sounds]

- Nastassia Patin:

-

So it’s really taken us this long for us to fully appreciate the complexity and the diversity of microbiomes and how important they are to ecosystems. [Upbeat music]

- Renay San Miguel:

-

As you’re using this 21st-century kind of genetic-related technology to study some of these habitats, what were some of the main points that you found?

- Nastassia Patin:

-

We found that the community is very dynamic, so it can shift over relatively short time scales, but the dominant members, usually the top two or three species are all the bacteria that you would find in the ocean, so these are marine organisms that are just showing up at different levels in this aquarium marine system. We were just getting kind of a baseline for what is a healthy aquarium microbiome, so we got a sense of who the major players are, how they relate to things that live in the ocean, and how those dynamics change over time.

- Renay San Miguel:

-

During their months of study, the researchers saw so-called bloom events, periods where certain bacterial communities overflowed their boundaries. They took up more space than they were supposed to within the microbiome. I asked Patin if these bloom events were ever a cause for concern.

- Nastassia Patin:

-

What we saw in the bloom event was just kind of a natural increase in certain populations, very similar to things you would see in the ocean all the time here in the aquarium. Those become a little more concerning because they affect water clarity which is really important for visitors to be able to fully experience the exhibit, so we cared a little more about that than we would in the ocean. But in terms of any sort of unnatural shift or danger, that was never an issue. It was just a question of how can we understand these natural dynamics in relation to the kind of water clarity we want at the aquarium.

- Renay San Miguel:

-

So how important is this data then, not just to the Georgia Aquarium but to any aquarium out there? Why do they need this information?

- Nastassia Patin:

-

We were really just getting kind of a baseline foundation of what is a healthy microbiome in a saltwater aquarium. And that was really completely unknown before this. So while we knew more or less the kind of numbers of the bacteria and certain chemical parameters that we want to keep in check in this system, just having this baseline knowledge of who these beneficial bacteria are, and what they’re doing in the system, is going to be hugely valuable for anyone trying to keep a large saltwater aquarium. [Sounds of aquarium visitors, exhibit music]

- Renay San Miguel:

-

Even though as a marine biologist, Patin is focused on what’s in the world’s oceans, she considers herself fortunate that Georgia Tech and the Georgia Aquarium are not only close geographically, but also on the same page when it comes to microbiome science. She finds the arrangement valuable for the kind of long-term study she is undertaking with her fellow researchers in the School of Biological Sciences. What more do you want to study regarding aquarium microbiomes? What more needs to be learned?”

Nastassia Patin:

Nastassia Patin:-

Yeah, we still don’t really understand why the community shifts the way it does considering how well-controlled the chemical and physical parameters are in the Ocean Voyager. So we have a hypothesis that it is closely related to the microbiomes as you alluded to, the microbiomes of the animals that are inhabiting the Ocean Voyager, and so the next step in this project is going to be looking at some of those animal microbiomes and trying to look for patterns between those and the water of the aquarium. So just a better understanding of those temporal dynamics and why they happen is probably the next step. [Sounds of students in the aquarium]

- Renay San Miguel:

-

Aquariums are great places, especially for kids to come and learn about these habitats, and learn about that symbiotic relationship between the animals you can see, and the ones that are so small that you can’t.

Nastassia Patin:

Nastassia Patin:-

That’s right. It’s a really special place, it’s a really wonderful opportunity for people in Atlanta who are not close to the ocean to get a sense of how beautiful and complex the ocean environment is, all the way from giant whale sharks down to bacteria. And so I hope the Georgia Aquarium incorporates some of this microbiome science into their educational displays. I think it would be really valuable for the public and for anyone interested in how the ocean functions.” 8:25 [Upbeat music]

- Renay San Miguel:

-

Patin and the other researchers will continue their Ocean Voyager studies. In the meantime, if you and your family find yourselves there, gawking at the huge whale sharks, or following Tank the sea turtle on his journey through the exhibit, remember what you can’t see — those microorganisms that also roam Ocean Voyager, contributing to its environment, and its health. My thanks to Nastassia Patin, postdoctoral researcher in the School of Biological Sciences. The study on aquarium microbiomes is found in the May 2018 issue of the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology, published by the American Society for Microbiology. My thanks also to the Georgia Aquarium for letting us conduct the interview there, as whale sharks, manta rays, and Tank swam nearby. Siyan Zhou, a research associate in the School of Psychology, composed our theme music. I’m Renay San Miguel and you’ve been listening to ScienceMatters, the podcast of the Georgia Tech College of Sciences. [Upbeat music]